Category: Methodologies

The SDLC evolution

- Software engineering is an art, there is no science

- we put what we are supposed to do on stickies, and the developers know how to work them

- why are they stuck to your monitor?

- so i know what requirements people tell me I need to create and complete

- I can never figure out you are working on, or does all this work keep coming from

- the cleaning crew lost my stickies

- we keep running late on our promised delivery

- we need project managers to manage your queue so we know what you developers are doing

- Looks like we need process and stages, so we know what the real requirements are, and have an official sign off

- Yea, no one should ever code unless we know what we want to build and how its going to get broken up

- Okay, it took 9 months to document everything we want, lets code

- ….another 9 months… code complete!

- hmmm, looks like we built something that would have been useful 15 months ago

- …and looks like no one really wants to use it the way we build it

- okay, so lets define a bit, code a bit, and deliver a bit

- great, that way we can deliver sooner and see if its useful

- hey, this is great, but can we do it faster and better? can we get rid of more processes?

- monthly products and feature sets released…

- ..wow, this is great, were pushing out really useful features based on customer needs

- yea, but all these sprints, and the time boxing, there’s too much structure

- there’s gotta be a way to be even faster, leaner

- yea, is there a way to make these sprints visual? and the work to be done visual?

- yea I’m very visual, i could just look at a board and understand what i need to work on next

- how about a big board with stickies?

- that would be great, we can have a to-do section with all the stickies that need to be done. and then move…

- ..yes, yes! and we can move them from one area to another., and we can write our name on the sticky

- and we can really focus on the stuff that we are working on… and…. and… and…

- …this will work,

- ……if we all understand and know how to work these stickies

- …wonder why no one thought of this sooner

Kill the (process) champion

This isn’t anything new: Individual or a group of individuals (champions) see the benefits of process improvement, understand process improvement, and want the organization to benefit from process improvement by implementing process improvement. – What a novel idea.

In order to successfully implement and benefit from process improvement, its imperative that management sponsors the process improvement initiatives/activities. If management, or (in a smaller company) the owner does not see or understand the benefits of process improvement the truth is that it will never be successful.

Champions who try to implement process improvement by themselves will lose the motivation for (process) improvement along the road as they get busy with tasks and other responsibilities; this is especially true when they are going to be the only ones who are making the effort.

For example, an individual (software developer) trying to sponsor process improvement themselves to their own work, working for a company that has no form of formal requirement gathering or does not follow a software development model will soon get tired of putting in the effort (to gather requirements formally) as it will go unnoticed and unappreciated (maybe even criticized).

There might be even cases where the organization is so small (agile would work great here) that it would be impossible to place a “formal” process improvement methodology or cases where the organization feels that the processes they have right now are “perfect”; even though they might not be.

To determine if process improvement is required we can use the history of how well past projects went, under budget, over budget, issues that were faced and so on. We can also measure certain things and create actual results that tell us how good or bad our current process actually is.

It is always easier to explain your point to upper management when you have actual data and visuals such as charts that can be analyzed and used to substantiate your point; this is where measurements come in. Measurements themselves can be a complex and important tool that can be used in process improvement models such as CMMI, but it is not until level 2 and 3 (in CMMI) that you actually get to make use of those measurements. At some point (idea for another post) I will discuss how quick and dirty measurements can be put in place without too much of a hassle (and measure process without process). Not everyone is a “process” person and fail to understand the importance of process (and a formal SDLC).

Many will however understand results obtained from the measures when they are presented and used to talk about costs, budget, resources and timeline’s.

Application Lifecycle

SDLC along with the words “Agile”, “Iterative”, “Kanban”, etc are, in my opinion buzz words. You can pick up a book and learn “Agile development”, you can take a few courses and get your “Scrum Certification”, but following the documented approach, as is, will only get you so far.

To really understand SDLC you have to get into the guts of how things really work; why do people do things the way they do and understand the “natural processes”.

For Start-ups, small companies, new companies, walking in one day, or starting of with something like “We are going to follow agile development”, works. It works real well because they choose to start with the textbook definition; it works real well because you have new developers who will be agile and flexible, and do things the way you choose to do. For such an environment, someone can walk in and make sure that things are being followed the way they are supposed to be; but unfortunately, this is not how it works when you try to take something that has been running for a (very) long time and you try to make it different.

As an example, look how some auto manufacturers have decided to implement and offer “high MPG vehicles”; some chose to restart and build a brand new vehicle; others attempted to re-purpose or salvage their offerings.

So talking about SDLC methodologies; Who really wants to follow a waterfall model? that makes you sound too outdated and boy, I wouldn’t want that on my resume. (Sarcasm). For many, waterfall is still the best methodology but they still want to move to something that’s more agile; and there is no harm in doing so, just as long as you understand and implement something that works well for you.

Now, to build something that works well for you, you really must understand YOUR current “Application Lifecycle” and see how it can be optimized. SDLC is just a very small part of the “Application Lifecycle” and once you understand, document and optimize your “Application Lifecycle” you can focus on modernizing your SDLC.

So, to build the example of understanding the “Application Lifecycle”, I will draw up a few diagrams. I will focus on the positive paths and not the negatives so that the model doesn’t get too complicated and I will also make some assumptions/skip extensive detailing, saving that for a separate post.

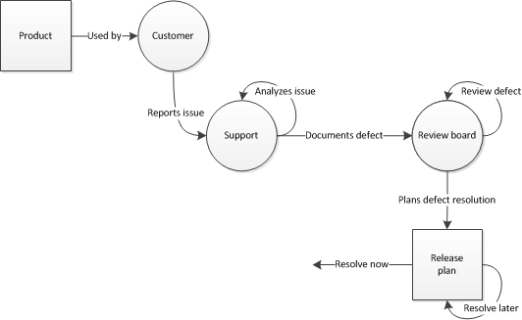

Starting the cycle.

- Once you have gone through all the (painful) steps of creating a product (in no order: Sales, Requirements, Dev, Qa, Test, Release, Etc) you end up with Product

- Customers use this product and they

- Report issues

- Reported issues go to your support team (hopefully)

- and the support team analyzes these issues.

Pretty simple right?

You have now documented the beginning of the cycle as after product deliver, you are getting things back that require work. So what does support do after they Analyze the issue?

- Confirm the issue and provide additional documentation (if needed), sending it to

- Some review board, or decision maker as to what to do with this supposed issue, and determine if its something that needs to be resolved now (defect) or something that needs to be done at a later time (enhancement), or maybe you do not want to do it. In any case,

- The review board makes a decision in regards to releasing it (now).

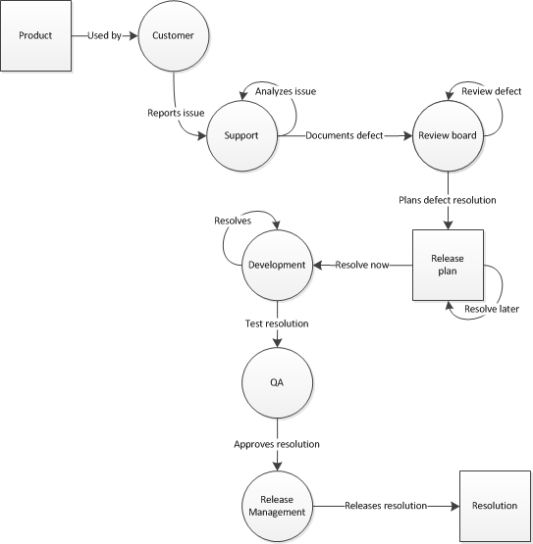

At this point, hopefully there is some queue setup that allows intake of things for development to work on as they will trickle things into their work queues (depends on what SDLC methodology you follow)

- Development picks up work and resolves the issue; after the issue is resolved, it is

- sent to QA for additional testing, and once

- QA approves the resolution, its

- given to Release Management, who then

- releases the resolution

- giving you a packaged resolution.

All this assumes that there was actually a code defect, and that it required immediate resolution as it was critically impact a live customer. Things get a bit more complicated when you bring enhancements, non-code issues, and other things into the picture.

Also, big “hand waves” are done at various points in my flow, for example, the following things need to be looked at as well

- How is the intake of work managed and prioritized, and by who?

- What is the regression/integration process?

- Who manages the movement of the issue from one area to another?

- How are issues that should not go to the review board handled?

- How does the information go back to the customer?

- How is information distributed to other customers?

- … and so on….

Understanding the Application Lifecycle, really does take “process improvement” to the next level as it allows you to follow several different best practices when it comes to SDLC or even the Organizational Lifecycle; For some organizations, they have a dedicated Business Process Office (or process office) that is responsible for looking at the big picture and ensuring that process is continuously optimized and improved.

So the next time you find yourself, wanting to “improve things” ask your self, “how big” of an impact you plan to make.

Being involved in such efforts right now, I wish you good luck.

Software Development Life Cycle VS Application Lifecycle Management

The Systems development life cycle (SDLC), or Software development process in systems engineering, information systems and software engineering, is a process of creating or altering information systems, and the models and methodologies that people use to develop these systems.

In software engineering the SDLC concept underpins many kinds of software development methodologies. These methodologies form the framework for planning and controlling the creation of an information system: the software development process. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Systems_Development_Life_CycleApplication Lifecycle Management (ALM) is a continuous process of managing the life of an application through governance, development and maintenance. ALM is the marriage of business management to software engineering made possible by tools that facilitate and integrate requirements management, architecture, coding, testing, tracking, and release management. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Application_lifecycle_management

SLDC is focused on “Software” in development; its what you follow going from one phase of software development to the other; i.e. from scope & requirements to design to code to etc…

ALM is more than “Software”; its the interactions between various functions/teams that follows the life of the application; i.e. from support to development, development to QA or how things come in from clients as defects and end up becoming enhancements for future releases and so on….

There is a ton of stuff out there on SDLC; my next post will be on ALM and how one can setup workflows and events (there are tools out there that can help you) to automate and mange the ALM processes.

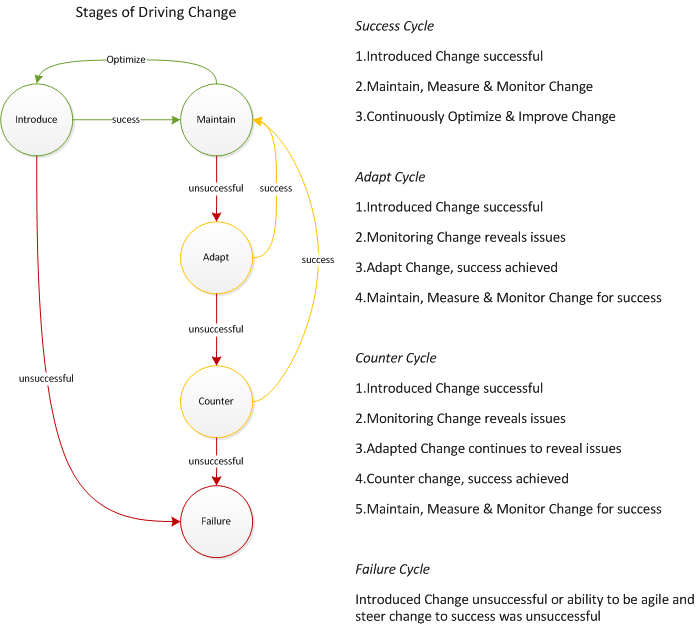

Making Changes: Change Cycle

To stay ahead (or on top) of the game, we must recognize that change is good and that we must be continuously improving the way we work. While reading a book “90 days” I realized that I had been through these stages multiple times, fortunately walking away successful. It also made me realize how close I was to a possible failure in some of the changes I had made and because of this realization; the Change Cycle will always be on the back of my mind when I attempt to drive Change.

I took the concept that was in the book and modified the terms as it was easier for me to relate the “change cycle” to something I already knew, the “process cycle”.

Here is what I do and have to say about process:

Good process should be well tailored to the organization that intends to benefit from it. Process is much easier to implement when its implemented in stages based on a feedback loop; When improving or introducing process, a big concern is usually how fast and how much? Well, too much too early generally results in resistance to change and too little too late results in process loss.

So what should be done?

A rapid agile approach should be taken when implementing process. Process is implemented and/or improved when the lack of process has been identified. Once an idea of what process needs to be implemented has been formed, the cycle starts with

- Introducing the process as a pilot, if the pilot is successful

- It should then be verified that it’s repeatable. If the pilot is successful and repeatable

- It should be formally defined and shared among the team as the formal process.

- The process should now be managed and measured to obtain metrics to figure out how successful it is, its ROI, etc. These metrics should then be used to

- Optimize and continuously improve the process.

The concepts of the “process cycle” for introducing a process are very close to the concepts of a “change cycle” for introducing a change.

In a change cycle, you:

- Introduce a change and if the introduction of the change seems successful you then

- Maintain the success to obtain stability. Once stability has been insured you

- Optimize and introduce other changes as needed; this is your optimal success cycle.

- Should the change not be maintainable, you will need to

- Adapt the change to make it maintainable; this is the adapting cycle.

- If you cannot adapt your change to be maintainable, you might have to

- Change direction and counter the change; this is the Counter cycle.

- If the change cannot be countered and be made maintainable, you will end up with a failed change. You can also end up with failure if your introduced change is not successful. A change can easily be unsuccessful if it’s too large; rubs people the wrong way, inappropriate, incorrect, etc.

Sometimes we start in this cycle at a completely different stage, for example we may realize that we have inherited a change put in place by someone else (different team, a VP, etc.) and we now need to act and adapt their request, or counter the change, making it successful. The 90 days book does a good job of giving a more general view of the change cycle; for me, the stage comparison of the two cycles makes sense.

The change cycle for making changes is just a small piece of the puzzle. How you go about obtaining buy in from your team, peers, and higher ups is another big part of the puzzle that will either result in success or failure. That will be a topic for another day.

Crouching Tiger – Flying Dragon

Not to be confused with Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon; or even a movie with a fancy/odd name…..

Crouching Tiger – Flying Dragon is the phrase I came up with while trying to give a name to a defect backlog bashing initiative.

Why Crouching Tiger – Flying Dragon?

The # of defects in the backlog is large; about 2200 cases large. Each case requires analysis, appropriate documentation and appropriate team assignment. For example a case may be a hardware issue, a question/concern, a software defect, incorrect client configuration, etc. This effort takes hours and in most cases multiple interactions with the client reporting the defect to obtain all the appropriate information. Putting all interruptions and need for multiple contacts aside, It takes at least 8 hours to document all the needed data. With the # of resources available, were looking at a year to get it all documented, assuming of course that no interruptions, PTO or other cases come up.

So how do you tackle this?

Ideally, if every case in the backlog had appropriate documentation and was assigned to the appropriate group, each group could then analyze all the cases and look for trends and similarities so that multiple cases could be grouped together.In addition to that, what has been learnt through metrics is that 10% of analyzed cases end up with the development team as software defects. From this 10%, only 52% turn out to be software defects…. So we are actually talking about 5% of the 2200 cases are actual defects….. If only there was a definitive way to magically find the 110 needles in this haystack….

In my organization there are support analysts and development analysts. Support analysts are on the front facing customers, development is in the back, non-customer facing.

The challenge is that we do not know which 5% are defects and we also don’t have time to go through all cases… So along comes Crouching Tiger – Flying Dragon.

Crouching Tiger: The support analysis team will spend 1-3 minutes per case that they are assigned to.. Were looking at a few hours per analyst…. While they spend these few minutes, the goal is to read the documented/reported issue and use their knowledge and experience to decide which group the case probably needs to end up. If they run into a case they believe is not a defect or is already resolved, it will be closed. We want our tigers head down, crouching, going through everything in their queues.

So where’s the flying dragon?

Flying Dragon: Once the tigers are done; we expect that we won’t have 5% of 2200; we may have 50%….. this is still better than having majority of the cases in an unknown state. Since capacity for analyst review doesn’t exist; effort must be made to have any resource help in anyway possible to eliminate the backlog. Let’s say we end up with 300 cases in development. Once we have these cases, we can run through them in multiple passes/phrases to get them appropriately refined. For example, pass 1 will focus on checking to see if development analysis results in dose closure (already resolved) and what component is the reported defect related to. Pass 2 focuses on refining the component to a more specific area. Pass 3 focuses on grouping similar issues or issues within a code area. These multiple passes represent the Flying Dragon and once we have the groupings we can convert them to projects that will be prioritized. The goal will be to resolve a defect area at a high level rather than a per case view; giving us a birds (dragons) eye view of what was broken.

Another motivator for picking this phrase was based on the fact that everyone in my org is functioning over capacity, multitasking and always on the go; having support stop and focus on going back to their queue backlog does make them crouching tigers for a bit. As soon as they are done the dragons will start flying through the multiple passes….. Getting us closer to success.